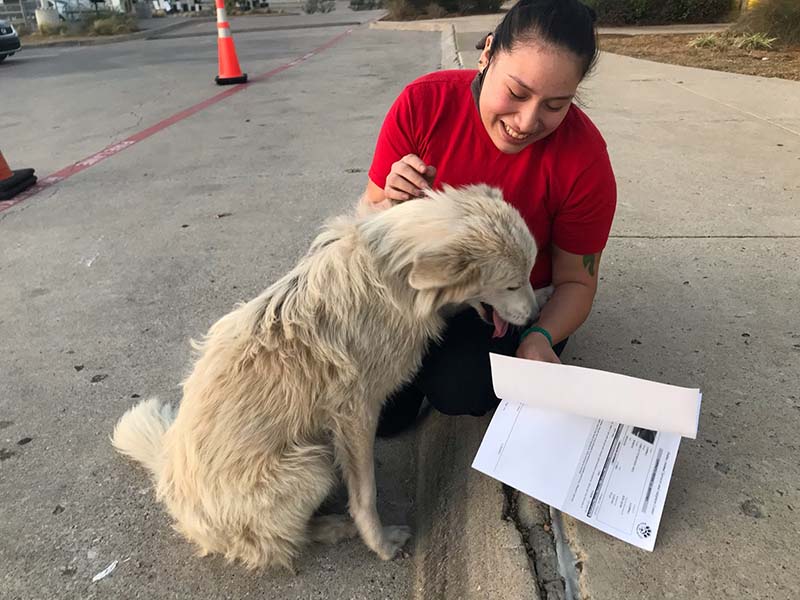

Getting Charlotte the dog back home to her family, after she went missing, was a relatively easy task for Dallas Animal Services, a tier 1 HASS pilot shelter.

That’s because Charlotte was microchipped, and the chip was registered.

But many lost pets don’t have a microchip or other identification. For animal shelters, this makes one of their most important functions—helping reunite lost pets with their families; known in animal welfare as “Return to Owner” (RTO), or, increasingly, “Return to Home” (RTH)—an acutely difficult challenge.

Enter data analyst Tom Kremer’s groundbreaking new study, published in Frontiers in Veterinary Science, which offers insight into how shelters can use data they are likely already collecting, to help more lost pets make it home—and keep more pets out of the shelter, in so doing.

Using HASS’s community-centered approach to animal sheltering as a launching point, “A New Web-Based Tool for RTO-Focused Animal Shelter Data Analysis” takes a deep dive into DAS’s data about where stray dogs are coming in from, and which of these dogs are being returned to their families (and which are not), to identify gaps and opportunities.

The findings are eye-opening. Among them: That 63% of the stray dogs DAS took in came from seven zip codes. Seventy percent of the stray dogs were found less than one mile from their homes. Forty-two percent were less than 400 feet from their homes.

Dogs in the northern part of Dallas were found farther from home (1.5-2 miles) than those further south (0-.5 miles). Of dogs who had a registered microchip, 70% were returned home, compared to 33% without. Only 30% of stray dogs had microchips, and DAS‘s highest-intake zip code “was on the lower end of the microchip rate compared with other areas across Dallas,” Tom writes, and so “it could be a good target to focus programs to promote microchip use.”

And regardless of where a dog was picked up, dogs’ length of stay at DAS was fairly uniform, the data analysis shows. Over 90% of the dogs who got home to their families, did so in less than five days.

“No matter where someone lives in Dallas, it takes them about the same time to retrieve their dogs from the shelter,” Tom says.

Tom built a dashboard to visualize the DAS results, which can be accessed here. (Tom says if other shelters want to see their data visualized in the dashboard—or if they have ideas for improvements or tweaks—they should email him at tom.kremer@minerva.kgi.edu.)

Returning lost pets to their homes was already a top priority for DAS. Doing so saves taxpayers money, increases the shelter’s lifesaving rate, and “honors the human-animal bond,” says DAS shelter manager Jordan Craig.

Participating in this study is helping the shelter think about how to do that even better. To identify obstacles standing in the way of returning pets to their homes, and target resources and services where they are needed.

For example, DAS staff is now going door-to-door in communities with low return to home rates to make sure families know how to find a pet who becomes lost, and asking members of the community to post to social media about pets who have been found. To spread the word, they’ve shared yard signs and have asked local businesses to relay information.

“We also started using the local Nextdoor platforms to target the area where the pets were found, both for microchipped and non-microchipped pets,” Jordan says.

While this particular study focuses on Dallas, the lessons are more broadly applicable. “Look at your data, figure out which animals aren’t getting home, and strategize from there,” Jordan recommends.

Gina Knepp, national shelter engagement director for the Michelson Found Animals Foundation and a founding member of the HASS executive committee, agrees.

Using data like this “has the potential to dramatically change how shelters approach RTH, the data being tracked, and allow for greater focus on those things which irrefutably increase an animal’s chance of being returned home should they become lost,” she says. “Much of our work in animal welfare is anecdotal. Having actual data to drive our decisions, where we invest our energy and funds could be a real game-changer.”

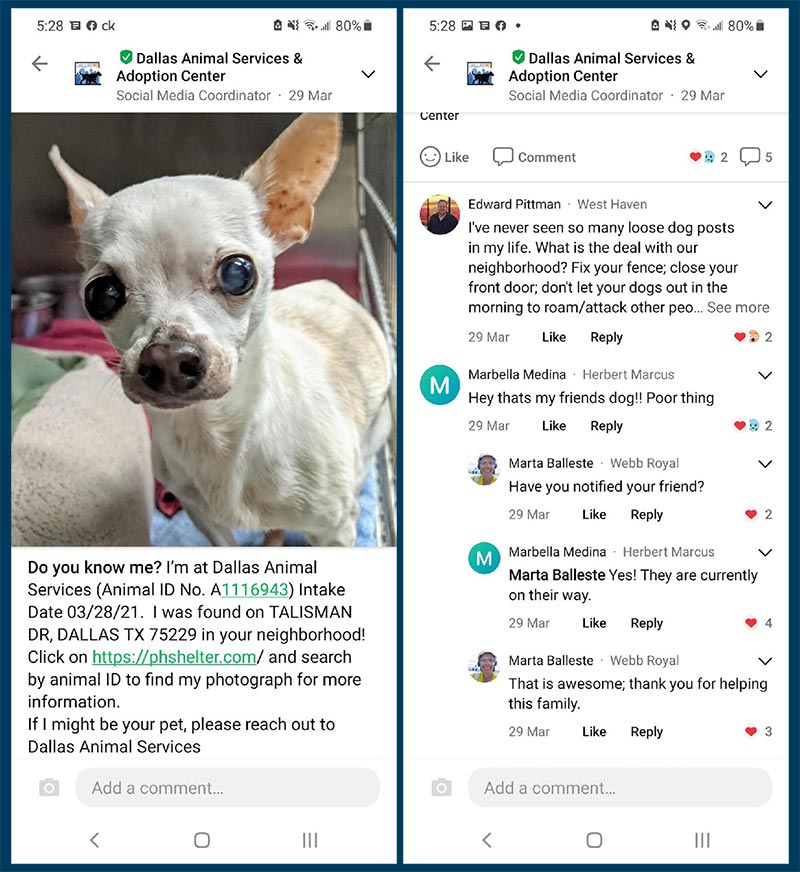

In fact, it already is. In March 2021, a Dallas resident found Cheddar the dog roaming loose. Cheddar was not microchipped. Using the new targeted strategies, DAS posted Cheddar to the Nextdoor page for the neighborhood where he was found. A friend of Cheddar’s owner spotted the post, and let his owner know where her lost dog was waiting. She came right in to collect him.

It turned out Cheddar lived less than a quarter of a mile from where he was picked up.